HISTORY/AFRICAAM 54S

From Stanford to Stone Mountain:

U.S. History, Memory, and Monuments

The future of America’s memorial landscape is a subject of intense debate.

In recent years, Confederate monuments have been lifted from town squares, as universities pledge to remove names and symbols of white supremacy from their campuses. At the same time, the National Register of Historic Places grows larger each year, new memorials are constructed, and old memorials are reclaimed, tagged with messages of resistance and protest.

Each of these sites has a history of its own, distinct from the history it purports to represent. How do societies remember? Who built America’s monuments and memorials, and to what ends? How have their meanings changed over time?

This course moves along chronological and thematic axes to explore these questions, surveying the history of memorialization in the United States. We will examine the “memory work” that informs various sites and acts of commemoration through a series of case studies, paying close attention to the interplay of race, gender, and nationalism. Drawing on a range of historical sources and approaches – from political cartoons, textbooks, and poetry to architecture, exhibits, and oral histories — together, we’ll build a methodology for recovering the layers of history behind sites and symbols of public memory.

Themes, questions, and sample sources below…

Week 1 | Frameworks

What is collective memory? How does it differ from individual memory? From history?

Week 2 | Remembering the American Revolution

Day 1: Imagined Communities

Day 2: “Declaration of Independence! Where Art Thou Now?”

Who was included in early articulations of the American nation? Who was excluded? Who got to decide?

How have oppressed groups used the politics of memory to advance their goals?

How do we study the construction of nationalism? What role does collective memory play?

What strategies can we use to read primary sources for motive/intent?

Sample Source: Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, July 3 1776, collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Electronic edition available at: http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/.

Week 3 | History and Memory in Antebellum America

Day 1: Writing History, Writing Memory

Day 2: Preserving History, Preserving Memory

Is a memoir a historical source? Is it inherently less reliable than a history textbook?

Can we read space the same way we read a historical text? What strategies can historians use to recover the meanings a particular place held for people in the past?

Sample Source: Emma Willard, History of the United States, or Republic of America (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co.), 1855. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hn23gz.

Week 4 |

Civil War Memory, Part I

Day 1: Remembering the Dead

Day 2: The Lost Cause, and Causes Not Lost

What were the cultural impacts of mass death during the Civil War? How did Americans choose to remember unprecedented loss?

More broadly: how was the Civil War remembered and forgotten in the decades after Appomattox? To what ends?

What is the Lost Cause? What were its historical origins? What role did historians play in advancing and resisting this myth?

What strategies can we use to analyze poetry and photographs as historical sources?

Sample Source: Matthew Brady, Wounded Soldiers in Hospital, photograph, c. 1860-1865, Matthew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Themes, National Archives and Records Administration. Available at: https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/brady-photos.

Week 5 |

Civil War Memory, Part II

Day 1: Monument Case Studies

Day 2: The Civil War in the Era of Civil Rights

How do we recover a monument’s meaning(s)?

How do we study historical silence?

Sample Source: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, sculptor, and Detroit Publishing Co., publisher, Shaw Memorial, c. 1900-1915, Boston, MA, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-det-4a25021. Available at: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016800398/.

Week 6 | Inventing Public Space, Part I

Day 1: The National Mall

Day 2: Case Study: The Lincoln Memorials

What kinds of sources and spaces project “official” memory? Who decides what is represented there?

What strategies can we use to analyze art, sculpture, and built landscapes as historical sources?

Sample Source: “Marian Anderson Sings at the Lincoln Memorial,” Washington, D.C., April 9, 1939, Hearst Metronone News Collection, UCLA Film & Television Archive. Available at: https://youtu.be/XF9Quk0QhSE.

Week 7 |

Inventing Public Space, Part II

Day 1: The Post-Slavery Plantation: An American Memorial?

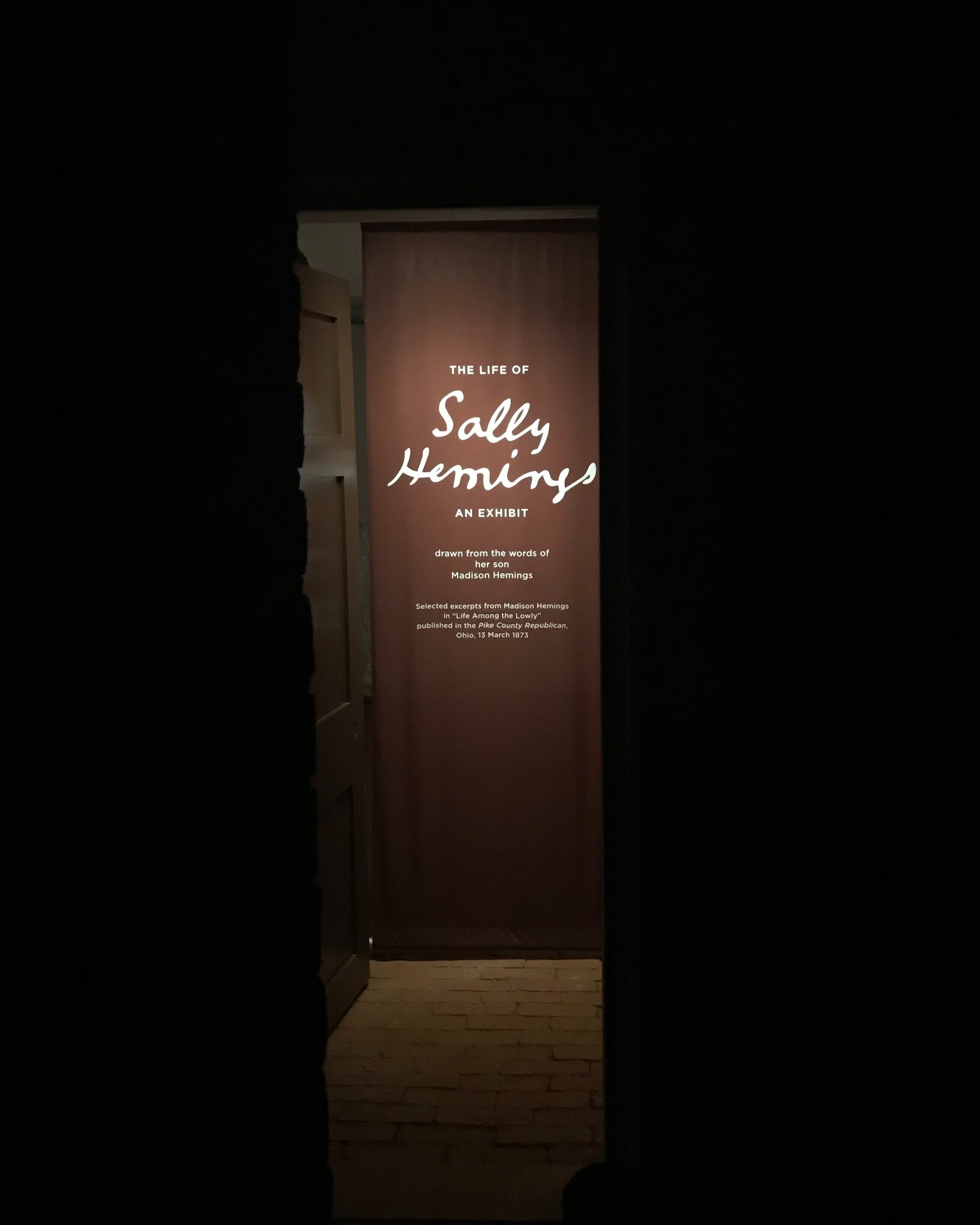

Day 2: Case Study: Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson, and Monticello

What is being remembered on the post-slavery plantation? To what ends?

Can a site of white supremacy function, today, as a memorial to the enslaved?

Sample Source: “The Life of Sally Hemings,” multimedia exhibit, Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello, 2018. Available virtually at: https://www.monticello.org/sallyhemings/.

Week 8 | “Here We Admit A Wrong”: National Memory in the Twentieth Century

Day 1: Remembering Japanese Internment

Day 2: Oral Histories

How has “official” memory of Japanese internment changed over time? How have new sources driven that evolution?

Does an oral history preserve memory? History? Both?

What opportunities and challenges do historians confront in using oral histories?

Sample Source: Noah and Hana Maruyama, “Episode 1: Rocks,” Campu, podcast audio, September 30, 2020. Available at: https://densho.org/campu-rocks/.

Week 9 | How Universities Remember

Day 1: Historical Injustice on University Campuses

Day 2: Case Study: Renaming Debates at Stanford

What is the history of the reparations movement? How does this history inform contemporary activism on university campuses?

Is it ever too late to redress an injustice?

How do we recover and write institutional histories?

Sample Source: Principles and Procedures for Renaming Buildings and Other Features at Stanford University,” Advisory Committee on Renaming Principles, approved 2018. Available at: https://campusnames.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2018/03/Stanford-Renaming-Principles-final.pdf.

Week 10 | Future Directions, Community Interventions

Day 1: An American Counter-Monument?

Day 2: Rebel Archives, Rebel Monuments

What is a counter-monument? How does it differ from traditional expressions of national memory?

How does silence enter an archive? Is it possible to identify these silences? To fill in the gaps?

How can material culture help us answer historical questions?

Sample Source:

Maya Ying Lin, “Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Competition drawing," photograph, 1980 [or 1981], Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-09504. Available at: https://www.loc.gov/item/97505164/.

Final Project

One of the central questions of this course is: how do you recover a history of memory? This assignment invites you to model a possible answer to that question, drawing on the methods we have discussed over the course of the quarter.

Your 8-10 page paper (or equivalent project — let’s discuss!) might consider a site or a subject of public memory in the United States (i.e. the Robert E. Lee Statue in Richmond, Virginia, or Independence Day celebrations). You should use at least five primary sources to make a historical argument that considers who is doing the remembering, and to what ends. You should also explore secondary sources (this may include chapters/articles we have read in class) to determine what historians have said about your topic in the past. What did they argue? To what extent do you agree or disagree?